By Miriam Martín

Translated by Lucía Salas

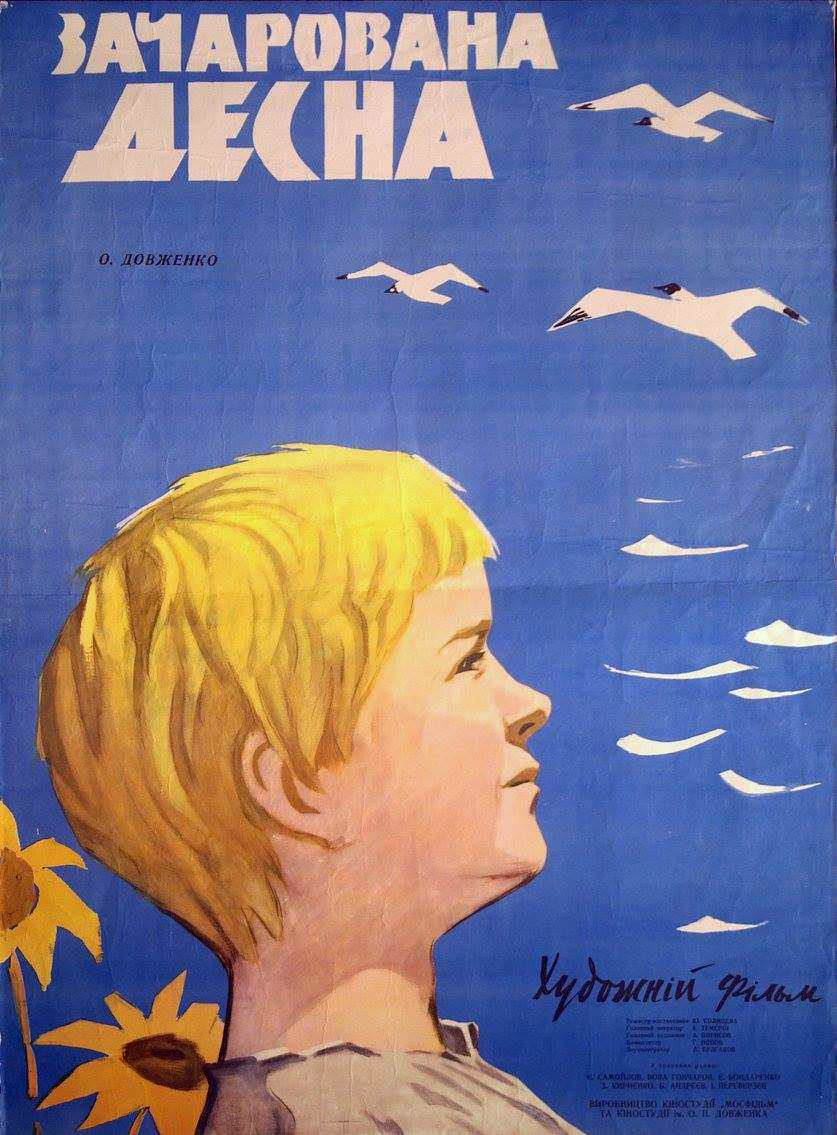

The Enchanted Desna (Zacharovannya Desna, 1964)

The Enchanted Desna (Zacharovannya Desna, 1964)

The boy Aleksandr sees forms in what is alive. In the bark of oaks and willows he sees men, horses, wolves, snakes, saints. He sees battles in the clouds between giants and prophets. All is ambiguous, in all there is a double life, all calls for comparison. The child detects in things the inclination to other things, the dream of other things. He sees in his peasant father a model to draw knights, gods, apostles, scientists, in spite of his wretched clothes; an ancient statue covered with rags. He hears two horses, abused by this father, say acutely that every time he raises the whip against them he is, in reality, punishing ‘his own misfortune’. But the proletarian horses do not only recognise those who resemble them. He also hears them talk about the time when they had beauty, that is, when they did not work. Of the time when they still had wings.

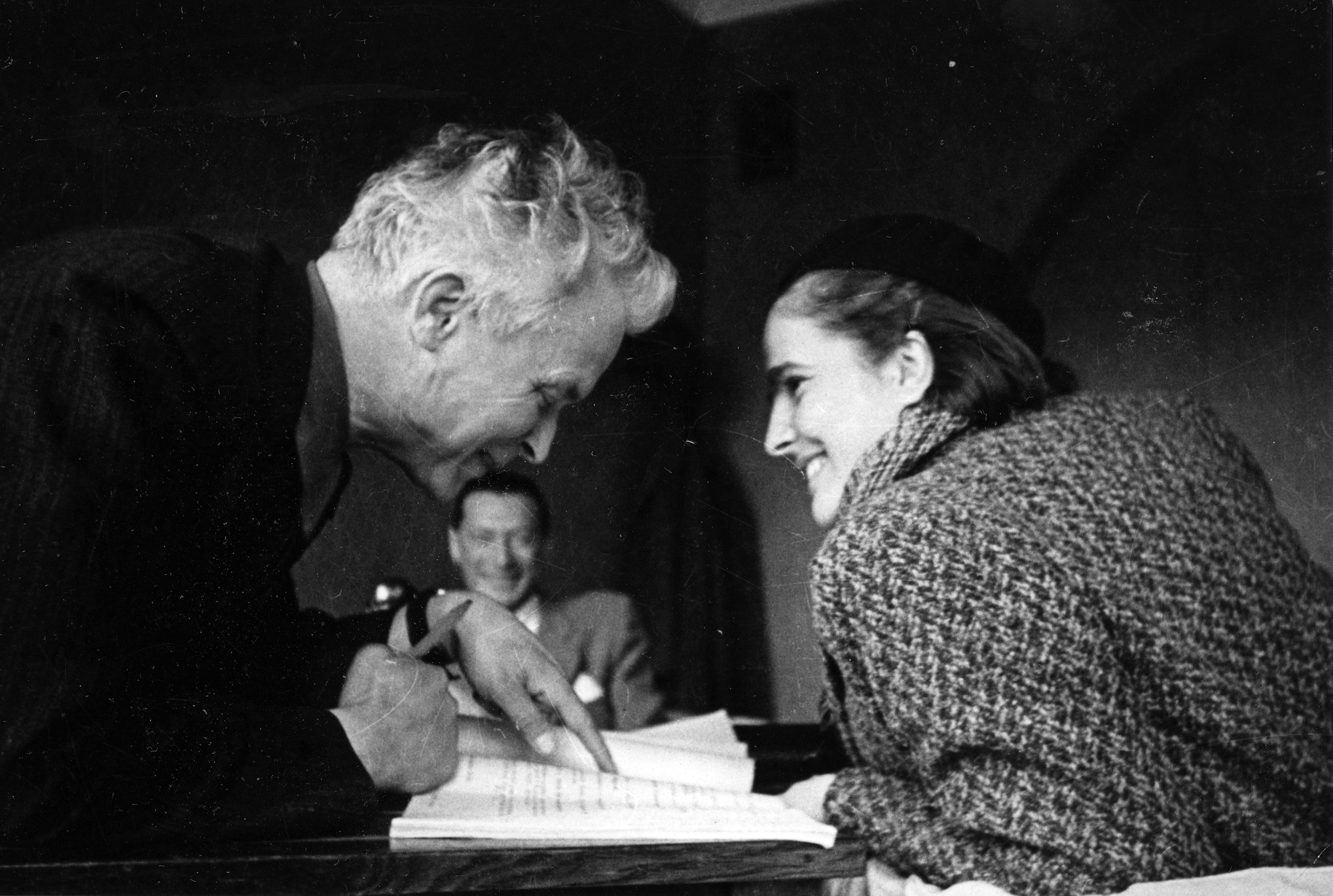

The boy Aleksandr is an adult who can still be a boy because he is an artist. Not a professional artist, let’s be clear, but an artist like Oleksandr Dovzhenko, who painted, who wrote, who made films, an athlete of sensibility and the only one of the usual great Soviet filmmakers who was born poor. In 1928 he married Yuliya Solntseva and in 1964, eight years after his death, she filmed The Enchanted Desna from his childhood memories. Mosfilm paid for the film and the phrases written in Ukrainian were translated into Russian (not all of them: if someone sings, they sing in Ukrainian). So, Dovzhenko’s childhood memories are not filmed by him, because he dies, they are filmed by Solntseva, because she loved him, and they are filmed in Russian because Mosfilm pays, except for the songs, considered perhaps untranslatable and free from any ecumenical function. The film is made of disidentifications.

The adult-artist-boy Aleksandr-Oleksandr moves in time and space. We see him in uniform in what was supposed to be ‘the last war of mankind’, fighting in retreat with a group of soldiers, crossing the Desna River with the help of the civilians he leaves behind. And he does not come out unscathed from their reproaches, he listens with an attention that causes him sadness and shame and yet he listens, he thinks of the Styx, the enemy fire lightens the transit between two worlds, Aleksandr notices that something new has ignited inside him. Communism is, above all, a matter of perception. And the artist bitten by communism comes here and there, does this and that, participates and observes his participation, does not neglect any possibility. From the trenches, he interrupts another night adventure on the river – his father takes him in a canoe, he is six years old again, asks the shooting star to fall and she falls, the fish to splash and it splashes – because a lion suddenly appears. In Ukraine. He imagines the lion and then a conversation with his inner editors, who ask him for verisimilitude, programmatic realism, not the dry realism of class-conscious horses. But why couldn’t he write ‘as a boy of the Desna, who wanted lions to roam everywhere in real life’? The film grants, amplifies this wish.

In borrowed words: When I was little, the grass was taller than me and was full of sky. Where is the grass’ sky, that zenith within reach? The cloud has risen to a devilish height. Yuliya Solntseva lowers for us the unreachable cloud, so we can feel the children’s feeling or even make our feelings child-like. Childhood happens out in the open, away from home, away from home. Running in fast motion through the sunflowers, shaking the apple trees in slow motion, hurtling downhill! The desire to put it all in your mouth. The secret corner where to go die when we misbehaved and were sent to hell, and we did not separate the words from what they give a name to, credulous, drunk with literarity, which is the greatest fantasy. Hell red, poppy red, sun red, the scythe’s ris-ras. Although the voice-over alternates verbs in the past tense, it is impossible to write off something that is offered to us with such concreteness. It is time regained.

In the end, the Desna is dammed. It progresses. Explosions and cement. The bulldozers devour the earth choreographically, the cranes dance. The workers throw sparkles, hanging from metal structures, like tumblers. There we find Aleksandr, naturally. And where is he going? He goes to a flood, half a century before. And it’s a party. What film that is for the construction of dams – favourable in its forms, where appropriate – would show you the everlasting spring floods as we dreamed of them as children? A different, better world, Venice. Entire families plus animals on straw roofs, children in trees and, along the now sailable streets, Aleksandr and his father coming to the rescue in a canoe. In the son’s eyes, the father splits into two once again: a Vasco da Gama who, lacking oceans, sank his ships in taverns. It is Easter and the priest, in charge of blessing the paska bread from roof to roof, has the deference to fall into the water and provoke a general burst of laughter. The adult-artist-boy says that those who did not live in harmony with the forces of nature, who did not freeze in winter, got soaked in spring, burned in summer and got muddy in autumn, do not know the joy of living. In his head, dialectically, there is room for what does not fit in the heads of the engineers. He bids us farewell, wishing us ‘power and clarity of spirit to appreciate ordinary beauty’. Was there ever communism in the Soviet Union? We do not know. But there were, of course, communists.

This text was originally published in Outskirts Nº1 - August 2022