Grappling with the Locarno Film Festival's Extensive Retrospective of Mexican Popular Cinema

By Nathan Letoré

By Nathan Letoré

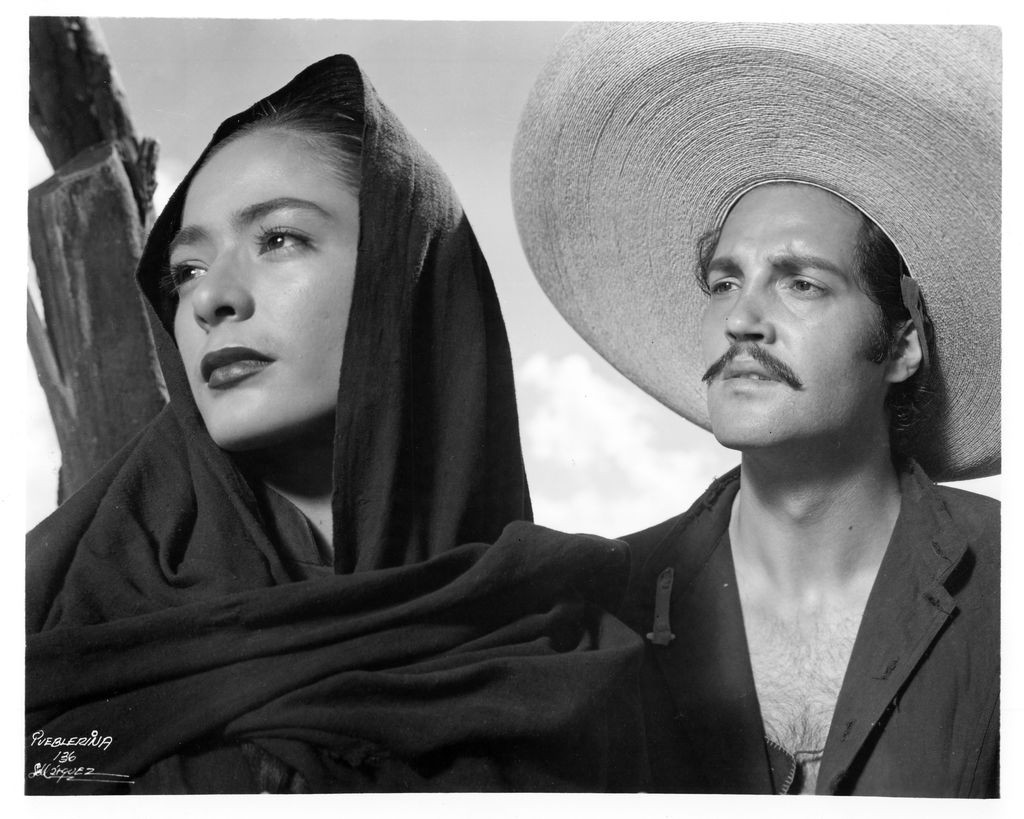

Pueblerina (Emilio Fernández, 1949)

Pueblerina (Emilio Fernández, 1949)As expected, the retrospective devoted to Mexican popular cinema at this year’s Locarno Film Festival was, like almost every year, one of the main highlights of the festival. ‘Spectacle Every Day: The Many Seasons of Mexican Popular Cinema’, curated by Olaf Möller, was ostentatiously conceived as a counter-history to most official histories of Mexican cinema, focusing on popular cinema in all its incarnations. This being Olaf Möller, of course, the term ‘popular’ was stretched in different and sometimes conflicting directions: few of the films belonged to the auteurist canon one discovers when digging into Mexican cinema for the first time, others were what one might call ‘cult’ objects, and others yet had once had meagre, one-week theatrical runs before slipping into oblivion. ‘Popular’, in this case, could diffract in many directions. A popular film can be a film that shows the lives of regular people; it can be a film that aims to reach these people; it can also be a film that draws a mass audience. But another, less immediately visible, axis tangentially cut through this: an image of Mexico's film industry, its bigger studios as well as its smaller ones, as a site of international exchange, of men and women making a film on their way to Hollywood or elsewhere, or coming back from it.

This certainly applies to one of the few figures viewers not so familiar with Mexican cinema might already have heard of, Emilio ‘El Indio’ Fernández, and his equally famous cameraman Gabriel Figuoera. Trained in Hollywood and having co-directed a film with John Ford, Fernández, however much he might represent and even symbolise the canon Möller was trying to shake up, is an unavoidable figure. To speak of a canon is to speak relatively, of course. It is not the same to speak, in Europe, of discovering Indian cinema beyond Satyajit Ray. For one, almost all of Ray’s films are available on DVD. Discovering Mexican cinema beyond Emilio Fernández, when very few of Fernández's films are available in any form, is a different story. Only one of Fernandez’s films was shown in Locarno, and far from his most famous. Pueblerina (1949) was introduced as one of the major ‘small films’ of Fernández's cinema, and of Mexican cinema more generally. And, sure enough, it was one of the supreme masterworks of the retrospective – what in God’s name does a ‘major’ Fernández look like? – and was none the lesser for our expectation that it would be. Aurelio, having spent six years in jail after killing the man who raped his betrothed Paloma, is released for good conduct. He heads back home to make good on his wedding. Paloma (the ‘pueblerina’ of the title) initially refuses him, considering herself spoiled by the rape and the child it resulted in, and the land-owning González brothers of Aurelio’s victim tell him in no uncertain terms he is not welcome back.

The introduction to the film stressed the hieratic postures of Fernandez’s cinema, tied to a certain mythology of the land and the peasantry inherited from the revolution. It is impossible to do without such a reading; Fernandez films his characters from below, monumentalising them either heroically or menacingly, and his close-ups are visions of lacerated souls yearning for each other or sizing one another up for the fights ahead. Music is omnipresent. In a central scene, Aurelio and Paloma tell the band to play on even though no one has turned up at their wedding. Though Aurelio is popular within the community, the Gonzalez family has issued a public threat: anyone helping Aurelio or being seen with him will be considered an enemy. The fiesta scene, staple of so many films in the retrospective, is here hollowed out, warped into a spectacle of desperate self-affirmation. Aurelio gets drunk and loud as the music swings back and forth between diegetic and melodramatic. Comparisons to John Ford are inevitable, and not only because of their joint directorial effort; Fernandez shares the same ability to capture a community's inner conflicts, to magnify classical tropes into heroic destinies that embody the community’s regeneration. Though he does not share Ford's easy-goingness or his ability to grant dignity to moments of quiet relaxation and the sharing of daily struggle, Fernández’s is similarly a monumental style, born of intensity and fateful decision-making: populist film- and myth-making of the highest order.

Similarly attuned to social fault-lines and the moral codes of rural labour was Julio Bracho’s Take Me in Your Arms (Llévame en tus brazos, 1954). The film was one of two in the retrospective starring Ninón Sevilla, one of the most compelling star presences of any studio system anywhere during the classical era. She here plays Rita, a fisherman’s daughter in love with trade unionist José, who is busy leading a strike against local land-owner and factory boss Don António. Don António offers Pedro, Rita’s father, who is indebted to him, that he will write off his debt in exchange for Rita’s services as a maid (the next step is left unsaid but still clear to all participants). Pedro refuses but Rita, unwilling to let her father's fishing boat be taken away, leaves with Don António at dawn. Unflinching in her refusal of Don António, she despairs at ever obtaining José's forgiveness, and finally drunkenly and unwittingly succumbs to Don António's foreman Agustín. Given no choice now but to use sex as a weapon, Rita makes it to Mexico City where she starts dancing and is ‘kept’ by political heavyweight Don Gregorio, who, for his election campaign, must rely on the local trade unions. Naturally, José is the leader and spokesman of these unions.

As is often the case in Mexico classical films, sex is a marker for morality as well as politics, a displacement onto the melodramatic female body of the boss’s power over the male worker. Bracho films Sevilla with gusto: low angles emphasising her vigour, her square jaw a mark of determination, her gaze burning through the frame with desire or defiance. Sevilla, as was mentioned in the introduction by Viviana García-Besné, spent her life in a relationship to the studio’s producer, whom she couldn't marry; his family disapproved at a union with a dancer and actress. She put up her own money to produce this film, an intervention which ultimately led to the break-up of the studio. Mapping this biography too closely onto the film is probably simplistic, but it certainly does illuminate a good deal, and it’s difficult to escape the sense that Sevilla is the key authorial personality behind the film (something which Bracho’s other films in the retrospective, as will be discussed below, seemingly confirmed). Here is a rare film in which exerting power upon a woman in sexual terms scars but does not degrade: Rita remains a fiercely proud agent of her own destiny, including when she breaks down crying in front of José, who is too tied up in class- and sex-based assumptions about her to believe her words. The film deftly navigates counterposed viewpoints, alternating not only between Rita's subjectivity and the way she is seen by others with startling ease, but also making clear the dialectic between other characters' perceptions of her and her own ability to shape the situation, something that is a stake in the narrative, an object of suspense. Take Me in Your Arms was doubtless one of the major revelations of the retrospective.

The other film starring Sevilla, and using her in almost exactly the opposite way, was Alberto Gout’s 1951 Sensualidad. A sleazy tale of manipulation by a dancer sent to jail and hell-bent on seducing and precipitating the downfall of the judge who sent her there… that is, until she falls in love with his son. The film holds together mostly through its actors: Sevilla, of course, with her broad, rigid jaw used here to denote maximum vulgarity and ruthlessness, seems incapable of giving anything other than an energetic performance that would grant the full force of conviction to each of her character's intentions. And that’s despite the Manichean script she is given to work with, which makes her into a sacrificial victim of the film’s reaffirmation of upper-class morality, killing her precisely when she stops being dishonest. Less exuberant but just as impressive is Fernando Soler as the repressed judge: instead of letting his stern, paragon-of-virtue pokerface crumble, he lets it sag more and more as the film goes on, his moral rectitude decaying but the imperative of appearances never disappearing.

Wetbacks (Alejandro Galindo, 1955)

Wetbacks (Alejandro Galindo, 1955)Social themes got a distinctly more academic, politically statist (and sometimes outright reactionary) treatment in two films by Alejandro Galindo. Wetbacks (Espaldas Mojadas, 1955) follows Rafael’s (David Silva) attempts to illegally cross the Rio Grande into the USA from Ciudad Juárez, and his disillusions with working conditions as an illegal alien once there. U.S. frontier authorities, invisible behind their glaring spotlights, are only barely more menacing than the human traffickers who thrive off the cheap, easily manipulated labour offered by migrants with no other choice. Friendship is offered to Rafael by a dandy hobo, who has managed to make it across the border legally but refuses to work, instead taking advantage of the superior American train system to hop around without ever indulging in the sin of labour. One aside about communism initially sounds fine enough with its promise of everyone being equal – that is, until one realises it means everyone working rather than everyone drinking champagne. That brief mention provides fair warning for Rafael and the audience not to draw undue political conclusions from his working experiences.

In many ways a lesser but still evident example of the genius of the system, Wetbacks showcases an industry's ability to probe social quandaries within certain carefully circumscribed ideological parameters. Rafael's is a tale of personal re-affirmation; he finds love with an American-born Mexican, María Consuela (Martha Valdés), whom he convinces to travel back across the southern border. Once back in Mexico, he finally asserts his dampened manhood by beating up his former boss (Víctor Parra, also memorably seen in El Suavecito [1951]) and rolling him into the river, where he gets shot by the U.S. border guards who mistake him for one of the wetbacks he had long been slave-driving. After this triumph, Rafael grimly watches as his boss is shot dead. He stoically declares it solves nothing; everyone else cheers. A prime example of ideologically having your cake and eating it too. Far more haunting are the scenes of Rafael's work in the Arizona desert, and of the empty, despairing moments spent watching on as a convoy of prostitutes is brought in to distract the men. Close-ups ooze sweat and grime, heat drives everybody crazy, and a tracking shot that shows men sleeping under the train, alongside the tracks they have just laid, ties up togetherness and alienation, work and rest, makeshift joy and real despair in a single image.

Galindo was, like Julio Bracho, one of the directors given several slots in the retrospective. In both cases the gap between the major work and then the minor was astonishing, opening up questions about the less satisfying aspects of a retrospective which, in its better moments, was very satisfying indeed. Bracho’s The Pharaoh’s Court (La corte de faraón, 1944) is a sex comedy based on a 1910 play in which a spirited and very sexy slave is to be married to an impotent general. Zaniness, the focus of Möller’s introduction, certainly is on full display. Talking of sexual innuendo would be to get the tone wrong: jokes are full-on bawdy, punctuated heavily by reactions to the camera. The rhythm is not so much frantic as panicked, rushed rather than speedy. Maybe I was too tired; I didn't laugh once. Galindo's The Mind and the Crime (La Mente y el crimen, 1964), at the other end of the spectrum, was an example of a film that, at the time of its release, sank without a trace, begging the question: what makes it ‘popular’? A hallucinatory hodge-podge of pseudo-scientific pronouncements about the criminal mind (of course tied to prostitution, sexual fragility and perversion, and the lower depths of society, and duly justified by shots of covers of the latest books by ‘world-renowned’ psychologists), Galindo’s film is a failure as a cinematic enquiry into crime, and only works in fragments—say, as a collection of bizarre but deeply striking mood shots.

There are quite a few possible explanations for such wide dissonances: a focus on lesser-known studio hands, of course, and the possibility of investigating which of the various genres these directors were capable of working in, and that studios were capable of producing. An attraction for the bizarre, for the eccentric, the unexpected. Probably, too, a willingness to discount traditional definitions of aesthetic value in order to find value in and reclaim seemingly unworthy objects. All of which are objectives which, theoretically, resonate or have resonated with me as a cinephile. Yet it was difficult, when faced with some of the actual films, to shrug off the feeling of frustration, a sense of missed opportunity at some of the pathways along which the retrospective embarked.

This, of course, is probably tied to my own knowledge and preferences as a viewer, as well as my own itinerary as a cinephile. The retrospective's aim, as set out by Möller in his opening contribution to the festival’s public roundtable, was to eschew the twenty or so classics that ‘always get shown’. This makes perfect sense... if one has seen those twenty films (a safer assumption to make about, say, Japanese cinema than Mexican, at least in Europe). If not, one faces the conundrum outlined above with regards to, to restate the example, the non-availability of almost all of Emilio Fernández’s films on DVD or Blu-ray (which is not an end in itself, nor a perfect measure of mainstream awareness of a director, but a telling indicator nevertheless). This begs the question of just how ‘canonical’ these films are in a European context; making this retrospective feel at times like a counter-hegemonic proposition to a hegemonic position that has yet to be built.[1]

One of the consequences of this curatorial choice, then, is to provide, if not a better picture of Mexican cinema than ‘the classics’, at least a more varied one, fuller in terms of genres and registers. The question of quality – or beauty, or aesthetic power, or whatever you want to call it: that inescapable bugbear of film criticism which one would, theoretically, intellectually, like to be rid of but which one can never quite shake off – as it lies at the heart of why we are cinephiles and not cultural studies scholars. In this perspective, it becomes incidental; the films are not selected simply for their ‘worth’ however defined, but for their ability to flesh out a picture of an object, Mexican cinema, evidently in need of fuller exploration in general. At this point, one clarification is necessary: my critique is not, though it might sound like it, an invitation to remain safely within the terrain of the ‘classics’. Rather it is a critique of the idea that moving beyond the classics would seem to imply sacrificing the criterion of quality. Take Me in Your Arms and Wetbacks were prime examples, and more will be discussed below once frustrations have been vented, of moving beyond ‘famous’ titles and providing aesthetically worthwhile discoveries – something not all, or most, titles could lay claim to.

Is this a socio-historical view, in which the film has value based not on aesthetic value but on its sheer existence as a forgotten work? Not completely, of course: Möller is a famous iconoclast, constantly seeking reappraisal of what he considers established aesthetic judgments. But it is partly the idea nevertheless; Möller, in the roundtable, again expressed nostalgia for a time in which cinema was not divided into different target audiences, and how this nostalgia rests on the idea that cinema was, back then, a way of making sense of the world, or at a prism through with it could be approached. Understanding these films, today, becomes a way of understanding the world of the past. Fair enough, but I guess that what I look for in cinema, at this point in my cinephilia, is not a full understanding of the world but the construction of a gaze onto it. Put another way, I feel sympathy for the idea that seeing everything, making aesthetic quality an incidental concern, allows one to understand the world more fully, and the voracious completism the idea entails... but I also don't believe in it anymore. The idea belongs, maybe, more to academia, its encyclopaedic cultural studies departments, and their belief that understanding the history of aesthetics is equivalent to understanding social developments. This is an assumption that is only partly verified and which obfuscates as much as it illuminates. It’s also not cinephilia, or at least my version of it. Concern for finding beauty wherever it hides is not the same as declaring all maligned objects beautiful, nor is declaring any object worthy of exploration the same as declaring any object worthy of appreciation (and thus inclusion in a major retrospective of a relatively neglected national cinema).

The King of the Neighbourhood (Gilberto Martínez Solares, 1950)

Lest the preceding few paragraphs be taken as a conservative defence of high art against the plebs, let me link back with a clearly popular film which succeeded where the two I mentioned above failed, and work through the differences. The King of the Neighbourhood (El rey del barrio) is a 1950 comedy by Gilberto Martínez Solares starring Tin-Tan (Germán Valdés), a hugely popular comic presence I had never heard of and now want to know much more about. Here, he plays a kind, loving, and generous railway worker who also postures as a tough gang leader to a bunch of hoodlums who somehow buy it... until they don't. In the meantime, he has fallen in love with the new neighbour, who needs money to take care of her ailing mother, leading Tin-Tan to try ever more desperate heists with his gang – which then fail because of his foibles and deficiencies as a gangster. The film is twice as long as it needs to be in terms of pure plot, giving the lie to (or, when some of the scenes fall flat, confirming) the necessity of comedy being even more tightly paced than suspense. The King of the Neighbourhood is conceived not so much as a linear unfolding as a collection of sketches, many of which work thanks purely to the winning charm of its performer, whose extravagance never veers into the hysteria of a Jerry Lewis but remains on the level of winsome petulance. Some of the set pieces, notably Tin-Tan's overly eager attempts at burglary, are sublime. In one particular case, he poses as an Italian singing teacher, his every answer both a satirical characterisation of the persona he is parodying and a concrete way of getting out of having to sing himself. When his rich student, played by Famie ‘Vitola’ Kaufman, finally does start singing, Tin-Tan joins in with the histrionics, his antics both a parody of classical opera and a musically convincing and rhythmically fitting counterpoint to the main tune. Like Jerry Lewis acting out a CEO to the sound of a trumpet solo, this is hilarious because, beyond the successful parody, it works as music.

Santo vs. the Vampire Women (Santo vs. las mujeres vampiro, 1962) is something else. The film belongs to an era of cheapies made to tap into a newly emerging market. A coven of vampire women awakens from under a centuries-old curse. Their aim? To sacrifice a young woman, descendant of the one who sacrificed herself to keep them locked under the curse. Alfonso Corona Blake, the director, seems to have no evident concern for pacing whatsoever: the opening scene is fifteen minutes of vampirical exposition, creating its own temporality divorced from suspense. Santo is only introduced half an hour into the film, in one of two sequences (only the second one of which is related to the plot) that show him in the wrestling ring. He only intervenes twice in the plot, and in the second case, the climactic confrontation, he is immediately captured and rendered powerless by the evil vampires; his contribution is rather to distract them, in his incompetence, from the approaching dawn, which is what will ultimately foil their schemes. A far cry from both conventional heroism and conventional suspense then; Blake is seemingly more interested in the processes at play before his camera (vampiric rituals, the logistics of kidnapping, the physical truth of wrestling as spectacle, both in the ring and outside it) than in its ultimate narrative finality. Hard to call it major cinema, but just as difficult to deny that it doesn’t, on a scene to scene basis, have its own compelling power.

The Case of the Wee Murdered Woman (Tito Davison, 1955)

If my impatience with what quite often felt like strained originality or contrarianism is one of the threads of this text about Locarno’s retrospective of Mexican popular cinema, it's only fair to finish with an example of these very same objectives done right. Tito Davison's The Case of the Wee Murdered Woman (El caso de la mujer asesinadita, 1955) was introduced by Olaf Möller as a fever dream, unlike anything else we will have seen. Though there is the usual element of hyperbole to this statement, I can happily report that it holds. One can find elements of comparison, of course: the fervent love-beyond-death romanticism of The Ghost and Mrs. Muir (1947) or Pandora and the Flying Dutchman (1951), and, at the other end of the spectrum, the nonsense-as-freedom-comedy of some memorable secondary characters in Capra or Lubitsch, as well as the double-crossings of Wilder's. The mixture of it all is Davison's own. The plot: Mercedes lives with her husband Lorenzo and her three in-house servants. One night, after falling asleep on the couch, she is woken up by a couple escaping the storm, who are shocked to find her asleep in what they pretend to be their house; they insist that they bought after the previous owner's wife was murdered. Accompanying them is a man pretending to be a Sioux Indian, whose portentous declaration about the great plains becomes a running gag throughout. The dream-like fusion of factual absurdity with matter-of-fact logic in its organisation is vindicated when it does, after all, turn out to be a dream. But over the next few days, Lorenzo brings back both an attractive new secretary who is none other than the woman in the invading couple, and an American business partner, Norton, who has the physical traits of the Sioux Indian. As Mercedes grows closer to Norton, he in turn reveals having had a dream which announced his own death in a car accident, and hers by poisoning. If Mercedes and Norton grow closer by successive touches in which the tragically romantic element grows gradually more pronounced, Lorenzo and his secretary Raquel belong, despite the clear murderous direction the plot takes[2], to a quasi-slapstick tone of bumbling sexual attraction.

The mixture of tones the film achieves is astonishing: dreams are stumbled into without any of the classical fade-ins or effects, absurdity is quietly accepted, suspicions of murderous intentions give way not to suspense but to hilarious exchanges of teacups... Call it Peter Ibbetson (1935) meets screwball. If any film of the retrospective was able to show a national industry's willingness to go ostentatiously but deeply wild, to follow impulses through all their contradictory alchemy, to let working professionals use existing tropes to create truly original combinations, this was it.

[1] Of course, this argument is tied to me being a European viewer attending a European festival, and a non-specialist in Latin American cinema generally. I can well imagine the liberating, or at the very least intriguingly expansive, effect that such a retrospective would have and is having in Mexico, according to many of the participants at the roundtable.

[2] Interestingly, The Case of the Wee Murdered Woman was, with the rhythmically off but superbly shot and moody The Witch’s Mirror (El espejo de la bruja, 1962), one of two films in the competition making good Hitchcock's initially planned ending to Suspicion (1941): a wife knowingly drinks a glass of milk poisoned by her husband.