Revisiting Alfred Hitchcock's classic thriller, the opening film of Locarno76, to ask whether a film so full of sounds can truly be called 'silent’.

By Arta Barzanji

![]()

By Arta Barzanji

The Lodger: A Story of the London Fog (Alfred Hitchcock, 1927)

The first film I watched at this year’s Locarno Film Festival was not a compelling new release or world cinema discovery of the kind the festival is known for. Still, it constituted the most thrilling experience I had during the entire 12 days of my stay in Switzerland. The enormous 3200-sitter Palexpo FEVI, typically reserved for the premieres of films in competition, was filled to the brim for the occasion. Members of Orchestra della Svizzera Italiana took their places on the stage in front of the screen. A few decisive words appeared: ‘The Lodger: A Story of the London Fog… Directed by Alfred Hitchcock.’ Beyond the shadow of a doubt, it was bound to be a glorious afternoon.

V.F. Perkins argued that silent films often faced a choice between clarity and economy if they were to exceed a certain range of subjects and situations, especially those that didn’t fall within or close to pure action. Lacking the benefits of spoken dialogue and sound design, these films were left with no choice but to rely heavily on intertitles (often mixed with diegetic text) to fully convey the complications of the plot, or to forgo such plot intricacies in favour of more modest premises which were developed largely through movement and physical action. While this applied in manycases, it doesn’t seem to be a binary that ayoung Alfred Hitchcock was much bothered by. The reason could be gleaned from another assertion by Perkins: ‘The sound film’s innovation was not the talking picture but the audible picture.’ Working backward from this statement, one could argue that The Lodger isn’t a silent film, but an inaudible one. The film opens with a close-up of a screaming woman. Soon after we see police officers listening to off-screen eyewitnesses and taking note of their testimonies about the murder that has just taken place. Later in the film, Hitchcock suggests the sound of the titular character’s footsteps by showing others who take notice of the movement of a chandelier hanging from the ceiling. Hitchcock overcomes the two-fold problems of clarity and economy identified by Perkins by not conceiving The Lodger as a film without sound, but as a sound film that precedes sound technology. The images don’t substitute for the absence of sound as much as they imply the existence of specific sounds that we aren’t able to hear.

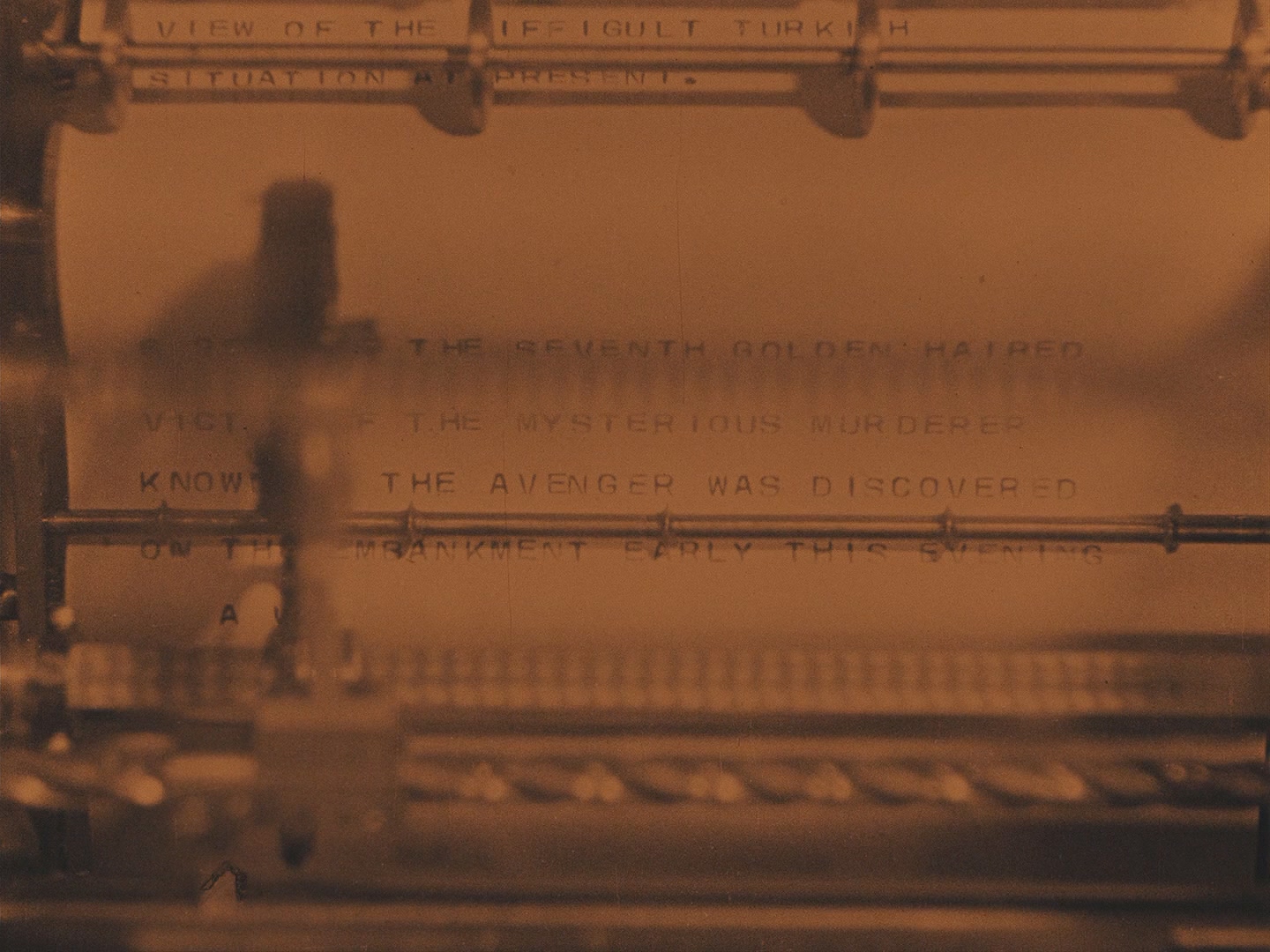

For a film with a relatively complex plot, The Lodger resorts to the use of intertitles only sparingly. Hitchcock takes advantage of newspapers, typed letters, and storefront signs to convey important information through language while reducing the need for intertitles. Yet language is rarely if ever used in this film to convey the emotions or desires of its characters. Problems of communication or the circulation of information become central both to Hitchcock and his characters. The Lodger’s second scene, following the murder with which the film begins, depicts the process of printing and distributing a newspaper. We’re introduced to the principal female character, Daisy, as one of these papers reaches her workplace, which alarms her about the serial killer who is still at large. Thus, the subject of the plot (murder of blonde girls) and the apparatus for its conveyance (newspapers/cinema) are directly linked from the outset. The circulation of information within the world of the film isn’t simply about the content of what is being shared, but also about the apparatus through which that information moves. And this applies as much to the diegesis as it does to non-diegetic information.

If the newspaper is the device through which characters in the film learn about the murders, we as viewers perceive the workings of the narrative, to a large extent, through their reactions to these texts. Or rather, their reaction, as filtered through Hitchcock’s image-making instrument, which presents a vision that’s at once objective (the language) and subjective (their response or interpretation). Hitchcock here combines ‘objective’ plot information (delivered through language) with the subjective reactions and responses of his characters and reintegrates the two, resolving both the problem of economy of expression (because it adds up to an efficient mode of communication) as well the issue of clarity (since the expressivity of his approach itself clarifies the meaning). The Lodger’s images thus acquire a double significance, functioning both as images for us, the viewers outside the film, but also as images for the characters inhabiting the film world.

Alfred Hitchcock’s cameo at the newspaper office

The Lodger’s images are often obscured, deformed, or ‘disguised.’ In the very first scene of the film, we see the distorted reflection of a man, something which frightens a witness as she momentarily mistakes this image for that of the murderer. The eponymous lodger makes his entrance framed within the front door of Daisy’s family home, against the hazy backdrop of the London fog. A hat and scarf cover most of his face, which means he (like the distorted reflection in the first scene) seems to match the description of the murderer provided by the witness in the first scene. Upon first learning about the serial killer and his fixation with blondes, a dazed Daisy says ‘No more bleach for me.’ It turns out that she isn’t a natural blonde, but neither the killer nor the lodger know that. To them, as well as to us, she represents the image of a blonde. In the context of Hitchcock’s career, this particular image would take on accrued significance with each new film. Still in the early stages of his career here, a young Hitchcock is already preoccupied with exploring the unreliability of images. Not of the falseness of a particular image, but the inherent potential of images to belie the reality of a situation. When the lodger enters the room he’s renting for the first time, he notices framed pictures of blonde women all over the walls. His disturbed reaction seems only to confirm our suspicion that he’s the murderer. Yet, later we learn that his sister, who was also a blonde, was murdered by the real killer. Ever since then, he’s been trying to think like the killer in the hopes of finally catching him. The lodger is also an image, with the difference that he’s an image self-consciously constructed to imitate the killer, based on the reports circulating about his appearance in the newspapers. One is the image of the prey, and the other is the image of the killer. She’s disguised when uncovered (since she’s not a real blonde), and he is disguised when covered (trying to imitate the killer’s looks).

If obtaining and communicating information is the main goal of the characters (and the main challenge of the film), confirming the veracity of that information is the challenge for the same characters (and the viewers). Since images are the primary means through which the film communicates information to us, the issue becomes one of the reliability of images. Within the diegesis, ‘image’ acquires more and more importance. Daisy’s jealous boyfriend, who happens to be a detective, falsely deduces that the lodger is the killer. As he stares intently at a footprint left by his new romantic rival, his thought process is conveyed to us as a series of images passing through the portal opened by the footprint in the form of a supercut of the various clues from throughout the film that suggested the lodger is the killer – to the viewers and the jealous detective alike. While by implication, we understand this is meant to be a visualisation of what the detective is thinking, what we literally see is a man looking at a series of images, images that appear to incriminate another man in a murder. Again, the image lies, misleading us and the characters alike to accuse an innocent man. This point is made ever more effectively since we have also, thus far, shared the detective's assumptions about the lodger. The disguised appearances of the killer, the lodger, and Daisy; the incorrect indictment drawn from the images in the footprint hole; all are followed by the handcuffs clapped on the lodger that give him a new false appearance of a convicted criminal. Believing the false image of the lodger in cuffs, the crowd forms an angry mob to exact retributive, vigilante justice. Hitchcock himself appears in a cameo as a participant, sporting a particularly frustrated look after they are stopped from killing the innocent lodger at the last moment.

The absence of audible language in The Lodger, similar to almost all silent films, leads to the use of written language as formal compensation. But The Lodger’s use of the written word is both quantitatively and qualitatively unique. In addition to the relative sparseness of the intertitles, instead of giving us concrete information about the plot or the characters’ state of mind, the words reveal, more broadly, aspects of the apparatus of the circulation of information and images. They aren’t simply words (as in a sound film), but images of words. Thus, they retain a potential for unreliability, like all the other images of the film. This is forcefully confirmed by the re-contextualization of a text introduced as a non-diegetic which turns out to be diegetic.

The Lodger began with flashing words that seemed to be mysterious and stylized intertitles: ‘To-Night Golden Curls’, followed by the close-up of a screaming woman looking in terror offscreen left at the killer looming over her. The film ends with the image of a woman (Daisy) being embraced by a man (the lodger), as the camera slowly tracks towards them. From the window in the background, we see the familiar words ‘To-Night Golden Curls’, flashing from the neon sign of a London nightclub. The camera gets close enough to cut the lodger out of the frame. Daisy’s eyes pierce through the upper left side of the frame to an unidentified point beyond it, as she wears a peculiar smile. Rather than a feeling of relief and safety, the ending carries a vague sense of unease and perversity. After all, if the central thesis of the film (and arguably, the central paradigm of Hitchcock's oeuvre as a whole) has been the unreliability of images, why should we trust the happy outward appearance suggested by this final image?